Search Results for 'Estates and Landed Society'

10 results found.

A prince arrives!

There was a curious sequel to the story of poor Michael Kelly of Mirehall, Headford, whom I mentioned last week. Kelly, a substantial farmer and horse breeder, won the ‘gentleman’s race’ at Galway in 1884. However the stewards refused to give him the trophy claiming he was not a gentleman. Kelly sued, and won his case.

A mad time of year in Galway

I do not think that it is a coincidence that the famous Galway Races coincide with the ancient festival of Lughnasa, celebrated on Garlic (Garland?) Sunday or, in the west, on the last Sunday in July. Máire Mac Neill, in her epic and scholarly study*, tells us that the date marked the most important farming benchmark of the year, the harvest, and it was robustly honoured. There were many Lughnasa gatherings throughout Ireland. Perhaps the most famous one in Connemara was at Mám Éan in the Maamturk mountains. People would camp out for days, musicians and hawkers would entertain the crowds; but the main event was a massive faction fight often resulting in serious injury or death.

The really ‘cultivated classes’ were the Irish themselves

“ We are no petty people. We are of the great stocks of Europe. We are the people of Burke; we are the people of Swift, the people of Emmet, the people of Parnell. We have created most of the modern literature of this country. We have created the best of its political intelligence...." so spoke out WB Yeats proudly, during a passionate debate in the senate in June 1925.

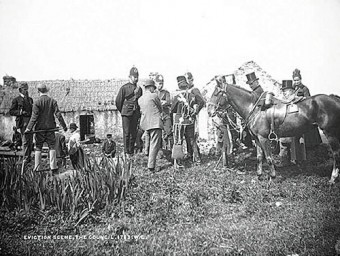

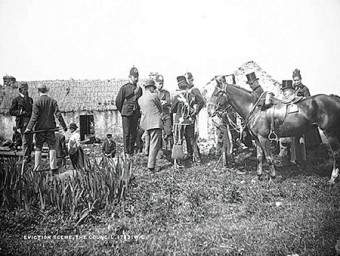

What more could a landlord do?

Despite some honourable exceptions the conduct of most Galway landowners to their tenants during the latter part of the 19th century was a disgrace. It led to disastrous social consequences. Although ultimately, the landed class were removed from their houses and lands, as a result of the Land War and acts of parliament; in many cases the peasantry too was decimated, demoralised and scattered to the winds.

What more could a landlord do?

Despite some honourable exceptions the conduct of most Galway landowners to their tenants during the latter part of the 19th century was a disgrace. It led to disastrous social consequences. Although ultimately, the landed class were removed from their houses and lands, as a result of the Land War and acts of parliament; in many cases the peasantry too was decimated, demoralised and scattered to the winds.

The Joyces of Mervue

The first recorded use of the name Joyce was Joy in the 13th century State papers. Sometime the name was rendered as Joy, Joyces, Jorz, Jorse, or the standard spelling, Joyce. The Joyces of Mervue were a distinguished branch of the family. Marcus Joyce, a rich merchant who bought land in County Mayo in the late 16th century, was probably the founder of this branch. About a century later, the Joyces emerged as a leading merchant family in Galway. Hardiman states that Joyce’s house was at the corner of Abbeygate Street and Market Street and that this family was head of the name. They were eminent wine merchants.

The Joyces of Mervue

The first recorded use of the name Joyce was Joy in the 13th century State papers. Sometime the name was rendered as Joy, Joyces, Jorz, Jorse, or the standard spelling, Joyce. The Joyces of Mervue were a distinguished branch of the family. Marcus Joyce, a rich merchant who bought land in County Mayo in the late 16th century, was probably the founder of this branch. About a century later, the Joyces emerged as a leading merchant family in Galway. Hardiman states that Joyce’s house was at the corner of Abbeygate Street and Market Street and that this family was head of the name. They were eminent wine merchants.

The pursuit of love among Galway’s landed society

Although rarely heard of today, ‘ breach of promise’ cases in the 19th century were quite common. A successful prosecution was a source of saving face, and social embarrassment; and could be of considerable monetary value if you were from the upper classes. All sorts of intimate details were revealed as the case dragged on, which provided delicious gossip for newspapers and their readers.*