Week VI

The alleged mastermind for the Maamtrasna murders was pointed out to Harrington. When he met this mysterious man he was coming out of one of his fields, bent under a big 'brath' of grass.

Harrington described him as 'tall, athletic, elderly, with iron-grey hair, dark complexion and rather prepossessing face.' His name was John Casey, the most wealthy man on the mountain. As well as farming he was the local 'Gombeen man,’ the money lender, a powerful man in any community. He was respected, and referred to as 'counsellor' meaning that he had a lawyer's smartness. On the surface he appeared to be well liked. He sometimes lent money without interest to help out an individual or a family who were particularly stuck. It is believed that he thought the murdered man, John Joyce, was a sheep stealer, and because sheep was the only source of revenue on the mountain, the crime was particularly despised. Had John Casey removed a common menace? Casey’s son, who often accompanied his father, had a vicious temper, and was feared by the community.

But when Harrington met John Casey, he was alone. He was polite. Admitted that he had paid the legal costs of some of the accused, but would not discuss the murder, nor why he didn't meet the costs of all the accused. Every question of Harrington's was deftly brushed aside, and after a while, Casey heaved the 'brath' onto his back and moved on.

Joyce's ghost

During the five hour journey on the steamer back to Galway Harrington told his findings to the journalist from The New York Times, whom he met in the Carlisle Arms that morning. In the journalistic style of the day, the journalist sets the scene of the two men talking 'within sight of the estate which Lord Mountmorres owned, and on which he was shot down; within sight too of the gloomy grey mountain further north, at the base of which the Huddy's bailiffs were murdered, sewn in bags, and cast into Lough Mask, and on the bleak side of which the Joyce massacre was committed ..'

The New York Times published its story October 12 1884; but it was also widely published, copied, and enlarged upon. Harrington also wrote a best-selling pamphlet, titled: ‘Impeachment of the Trials (1884 ), which was printed in both Dublin and New York.

Despite the overwhelming evidence that the trial was a disgrace, Dublin Castle refused to revisit the Maamtrasna Murder case. Two prisoners died in captivity. Michael Casey in 1895, followed by John Casey five years later. Both died of tuberculosis.

Then without any fanfare or prior warning, the last three prisoners, Martin, Patrick and Tom Joyce were quietly released. They had served 20 years' hard labour. They were called into the warden’s office, and showed three piles of coins on the table. They were told to take the money (just enough for their train ticket to Ballinrobe ), and go. The three men took the train to Ballinrobe, and walked the last 18 miles to their mountain home.

Unlike the Birmingham Six who were freed in 2005 after 16 years' imprisonment whose pending release was well heralded, they ran out of the Appeals Court in London to be welcomed by a huge crowd of well wishers.

But there was no peace for the spirit of Myles Joyce, a totally innocent man, hanged for a murder he knew nothing about. Within days of his botched hanging, and his anguished protests that he was innocent, his ghost was seen in the corridors where he was taken on his last walk to the gallows. His ghost was witnessed and seen by many people, prisoners, wardens, and the governor, and probably by Tim Harrington TD which prompted him to investigate the whole dreadful business of murder, informers, deadly enemies, and perjury, hangings and imprisonment.

Galway gaol closed in May 1939, but its high walls continued to be a forbidding landscape in the centre of the town. Work on the new Cathedral of Our Lady Assumed into Heaven and St Nicholas began in 1958. It was completed in 1965. There is a monument to Myles Joyce and others who died in the prison, in the car-park.

I remember standing with my father as a boy watching the walls come down piecemeal, hoping to see the ghost of the unfortunate Myles Joyce in the grey prison buildings inside.

Notes:

Little Patrick (Patsy ) Joyce, 12 years old, was the only survivor of the massacre. He was cared for by the Christian Brothers at Artane, but despite being available to be a witness at the trial, he was never called. He had always declared that he could not identify any of the murderers because their faces were blackened. If his evidence had been admitted it would render ridiculous the evidence of the Cappanacrehas who swore they recognised the murderers at a distance of some hundreds of yards on a dark night. The Crown solicitor George Bolton absolutely refused to allow the boy to testify; and he also warned Tom Casey, the informer, not to mention that the faces were blackened.

Of the Joyces who came home, after 20 years imprisonment, Tom soon left for America. Martin died within four years of TB, while Patrick died in 1911 aged 75 years.

Could the case be reopened, after all these years?

Two members of the House of Lords, David Alton, Baron Alton of Liverpool, and Eric Lubbock, the fourth Baron Avebury, did endeavour to have the matter raised, but it has not found the traction it would need to re-open the case.

Here are David Alton’s summary, and his report on the Harrington debate in the House of Commons October 24 1884:

‘The story certainly did not die with the death of Myles Joyce. Two years later, in August 1884 Dr John Mac Evilly, the Archbishop of Tuam, arrived in Tourmakeady to administer the Sacrament of Confirmation. Tom Casey – one of those whose evidence had taken Myles Joyce to the gallows, entered the church, and, holding a lighted candle, walked to the altar, and dramatically declared before the Dr MacEvilly and the gathered congregation that he had brought about the death of the innocent Myles Joyce and the imprisonment of four other innocent men. The Connaught Telegraph recorded this astonishing moment with an editorial entitled “the Law Made Murder.” Archbishop Mac Evilly wrote to Lord Spencer “in the interests of justice and civil society…and respect and confidence in the administration of law, to lay the whole case before your Excellency as it came before me.” He called for a full public inquiry. In a deliberate slight, Spencer delegated an official to reply to Dr Mac Evilly and insisted that no inquiry was required.

‘In a tough response, the Archbishop reminded the Viceroy that “It is hardly conceivable how, in the very jaws of death, (Myles Joyce ) would allow himself to be launched into eternity with a lie on his lips.” An even lower grade civil servant sent a six line reply again stating that the case would not be reopened. Politicians were by now also becoming involved. Tim Harrington, the Westmeath MP, promised to raise the case in the House of Commons. In 1882, during his protests against tenant evictions, Harrington had himself been incarcerated with some of the Maamtrasna prisoners and now led a vigorous and tenacious campaign to uncover the truth. Harrington travelled to Maamtrasna and painstakingly amassed statements, checked discrepancies and conflicting evidence. He issued a formal challenge to Spencer: “Officials who would acquit themselves of the blood of the innocent will need to vindicate themselves.” Later he documented the case in a booklet.

‘On October 24th 1884 Harrington secured a full parliamentary debate on the Maamtrasna murders. It raged over six nights. Harrington angrily pointed to the Crimes Act which “has worked manifold injustice” and in the case of Myles Joyce “has led to the execution of an innocent man.” Arthur O’Connor MP was the first to speak for the amendment proposing a public inquiry and said that although “It is impossible to bring back the soul of Myles Joyce; but if any respect for the law is to exist in Ireland, …legalized murder should no longer be allowed to stalk with impunity throughout the Island.”

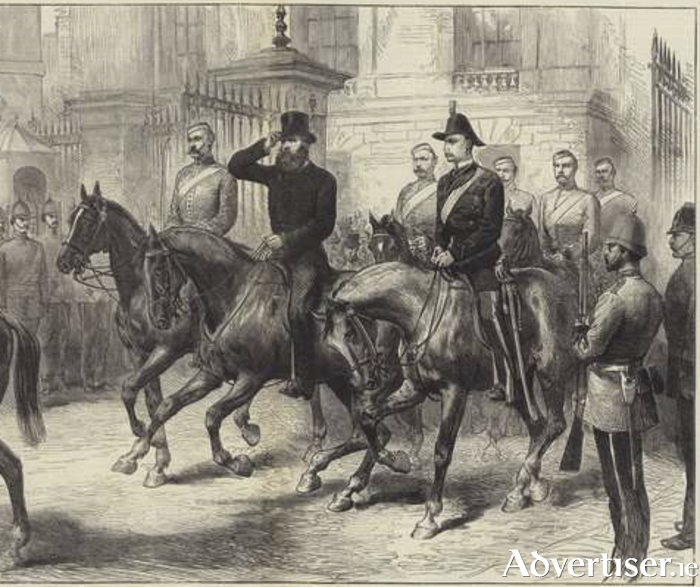

Many Irish MPs intervened, including Charles Stewart Parnell, and Harrington was given unexpected and strong support by the Conservative MP, Randolph Churchill. The debate brought the Prime Minister, Mr. Gladstone, to the Chamber, where he defended Lord Spencer, Irish officials, and the process of law. It wasn’t his finest moment but the Whips did their duty and the Government secured 219 votes against the 48 who voted for an Inquiry.

The outcome of the vote to one side, this case opened Gladstone’s eyes to the injustices in Ireland and paved the way for his support for land reform, for Irish Home Rule and his “mission to pacify Ireland.” ‘When recently talking about the case we pointed to the parallels with more recent miscarriages of justice – the Birmingham Six, the Guildford Four – and the implications for the use of capital punishment. And we were also both agreed that even with this passage of time, the injustice committed should not be allowed to stand. The true healing of British-Irish relations requires that, wherever possible, ghosts should be laid peacefully to rest and wrongs righted.’