‘My dearest mother,

I again write you a few lines, but oh Mother it is going to be the last. The last word to you on this side of the grave, as I am going to meet my great God tomorrow morning. But Mother Dear, don’t grieve for me as I am prepared to meet him who created me, to his likeness. But Dear Mother I know it shall grieve you all, but I ask one request of you not to worry but to pray for me because one prayer goes longer for me than all the sad tears that a nation could shed.

I am fully prepared for what poor Thomas wasn’t.* Just yesterday two years he was put before a firing squad. And I hope to be with him by the time you get this letter. Oh how happy he shall be to see me.

Dearest Mother I am sending you my Rosary beads. The beads I got from Father Kearney the day of Thomas’ funeral. I can’t stop but to think how happy he shall be when he sees me and knows that I have died for the same ideal that he died for.

Dear Mother I now finish by sending you Dear Mother my best love and also to Cissie, James and Joe. I shall write to them also.

So cheer up now we shall meet again in that happy land where there is no pain. Again I ask you all not to worry over this. Goodbye and God Bless, from your loving son, Hubert’. (Collins ).

This heartfelt letter was written from Athlone gaol this night, exactly one hundred years ago. Tomorrow, January 20 1923, Hubert (24 years ), Keelkil, Headford, was shot by firing squad along with Martin Burke (26 years ) of Manusflynn, Headford, Stephen Joyce (29 years ) Derrymore, Caherlistrane, and Thomas Hughes (22 years ), Castle Terrace, Dublin. They were all members of the North Galway IRA Brigade, fighting on the anti-Treaty side. If they were not aware at the time of their death, that their cause, however deeply and sincerely felt to be just, was losing the support of the country.

Castle Hackett

One week before their execution the four men were arrested following a widespread search after the burning of Castle Hackett House, one of the finest historic mansions around Tuam. It contained many historical articles, books and paintings owned by the Kirwan family, an original Tribal family, going back over the centuries, of which nothing remained. Raiders had called to the house on January 13 asked all the occupants to leave the premises and assuring the owner, Col Charles Kirwan Bernard, (a well liked man in the district ) that they meant him no harm but they feared the house may be used by the Free State Army.

No doubt the flames attracted Free State Army patrols, and over the following days a search through the villages of Cloonfush, Barnaderg, Cloonthue, and Lisavally the five men were arrested and taken to Athlone. There was no evidence any of the five were connected with the burning of Castle Hackett.

Former comrades

Following the death of General Michael Collins the previous August, the Provisional Government under the leadership of WT Cosgrave, Richard Mulcahy, and Kevin O’Higgins, took the position that the anti-Treaty IRA were conducting an unlawful rebellion against the legitimate Irish government and should be treated as criminals rather than as combatants. Even though they had all fought together in the War of Independence, it was a bitter ending to a successful campaign to see former comrades now as the enemy. It would take further executions, a total of 83 across the country, and scenes of extreme brutality particularly in Kerry, before an end to the madness was called. **

Practically the last to be executed in the Civil War, were another six Connacht men, Seamus O Máille Oughterard, Martin Moylan, Farmerstown, Annaghdown, John Newell, Winefort, Headford, John McGuire, Cross, Cong, Michael Monaghan, Clooneen, Headford, and Frank Cunnane Kilcoona, Headford, shot at Tuam Workhouse..

The six men were shot at Tuam on April 17 1923, when the Irish Civil War, had “effectively ended.” On 10 April 1923, the Free State Army mortally wounded IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch during a skirmish in County Tipperary. Twenty days later, Lynch's successor, Frank Aiken, gave the order to "dump arms".

Alarm in Galway

Almost a year before, June 22 1922, Galwegians had looked on with alarm as anti-Treaty forces began to take up positions in a number of buildings in the town, including the former RIC station at Eglinton Street, and were preparing for a fight. That morning Col-Commandant Michael Brennan, Free State army commander of the only major pro-Treaty unit in the west, under orders from Richard Mulcahy, entered the city with a large, well armed force. They immediately secured the county-jail, the courthouse, and the Railway Hotel. Shots were exchanged between the two sides.

Having seen the end of the War of Independence, and having voted by a substantial majority just weeks before for parties supporting the Treaty with Britain, this was a worrying state of affairs. Galwegians feared an all out pitched battle, followed by the horrors of the previous years of struggle. This time, however, the enemy was not Britain, but former friends and comrades. It was confusing.

The Galway electorate, now a single constituency, was emphatic pro Treaty. In the General Election just one week before the arrival of anti-Treaty forces, Galway had voted 24,717, or 67.7 per cent in favour of the Pro-Treaty Sinn Féin and Labour, combined; while the anti-Treaty Sinn Féin got 11,780 votes or 32.2 per cent. The biggest shock, however, for the anti -Treaty side, was that Liam Mellows, the leader of the 1916 Rising in Galway, a former Galway TD, and one of the most strident voices against the Treaty, failed to be re-elected.

Difficult time

In the event, however, it turned out to be a scrappy affair. A tentative truce was agreed. The anti-Treaty force evacuated the city at end of June, burning some buildings, including Renmore barracks, behind them. They attempted to attack parts of the city in the following days but were easily rebuffed. The anti-Treaty forces moved into Connemara where they had more support. It was a difficult time for everyone. Food supplies normally arrived by road and rail, but bridges were blown up and roads were blocked. People were exasperated and angry at the whole situation. The anti-Treaty forces continued on a trail of destruction. They attacked Clifden, and in an extraordinary series of ambushes and gun fights were eventually driven out, but they blew up bridges, burned old houses, mined roads, including burning a children’s orphanage.

Nora Barnacle.

Into the middle of the military situation in Galway, however, Nora Barnacle, and her two teenage children, Giorgio (17 years ), and Lucia (15 years ), arrived happy to get away from Paris, and all the fuss surrounding her husband’s book Ulysses which after long years of anticipation, had finally been published in February. Joyce begged Nora not to go to Ireland. He had a horror of violence and was worried for their safety. But Nora was determined. Dressed in their finest clothes (Nora wanted to show that after years of semi-poverty, the Joyces’ were doing nicely ), arrived in Galway at probably the worst time in the many years of conflict with Britain, and this time, in the middle of a vicious civil war.

They stayed at Mrs O’Casey’s boarding house in Nun’s Island, and although the children refused to go into her mother’s house in Bowling Green (they did not like the smell of boiled cabbage ), they waited outside while Nora enjoyed herself chatting to her mother and sisters Delia and Kathleen. She showed the children the Presentation Convent where she worked. They had their meals in local cafés. However, fighting broke out in the streets, and one evening, soldiers burst into O’Casey’s looking for a vantage point for an ambush.

That was enough for the Joyces. Georgio, who could not sleep hearing gunshots during the night, called all the waring factions ‘Zulus’, while he and Lucia rushed with their mother to get a train to Dublin. Leaving Galway was nightmare. As the train was approaching Renmore barracks shots were exchanged between Free State soldiers on the train, and anti Treaty forces along the line. The Joyces had to lie on the carriage floor for safety, as bullets zipped past them. They arrived in Dublin in a nervous state to be met by her generous uncle Michael Healy, who laughed so hard at their adventures ’that he nearly fell off his chair.’

It was Nora’s last visit to Galway.

Next week: Clifden is taken over by the anti-Treaty forces.

NOTES: *Thomas Collins was shot by British forces in Dublin.

** On January 7, 1922, the new Dáil Éireann narrowly approved the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which was to end the War of Independence. The Anglo-Irish Treaty gave the 26 counties of Ireland full control of its destiny, while the six counties of Ulster would remain under British control. There were other caveats too that rankled with the aspirations of practically half the Dáil deputies at the debate. Now, if the new treaty was accepted, all Dáil deputies were obliged to take an oath of allegiance to King George V, while the new Free State of Ireland would remain part of the British Empire, the same as Canada and Australia.

Michael Collins insisted that although the Anglo-Irish treaty did not deliver the ultimate freedom that all nations aspire to, it did provide ‘the freedom to achieve freedom’.

After a prolonged and passionate debate, the treaty was passed by the Dáil: 64 in favour, 57 against.

The general election, which followed on June 18, was seen as a referendum on the treaty. Seventy-eight per cent of the electorate substantially ratified the Dáil’s narrow agreement.

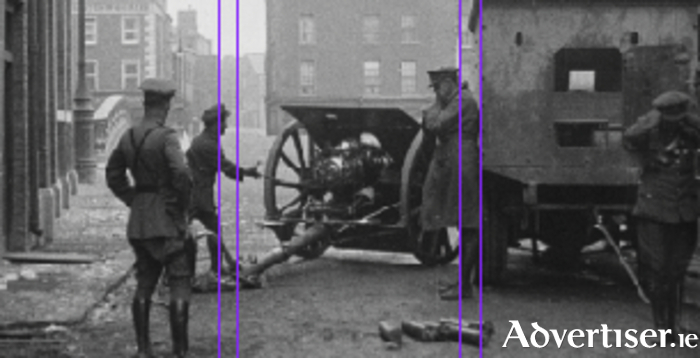

However, following the Dáil vote in Dublin a garrison opposed to the Treaty occupied the Four Courts. After months of negotiation, Michael Collins lost patience, and ordered artillery to fire on the historic building. Britain who had been watching developments in Dublin closely, and had a vested interest in seeing that the agreed treaty was followed through, lent Collins two 18 pounder Field Artillery guns which quickly brought the siege to a close. (The British army helping to dislodge the garrison at the Four Courts must have infuriated the anti -Treaty side even further ). That was the start of the Civil War which followed a similar pattern to the 1919-1921 conflict: with guerrilla warfare dominant in concentrated areas of the country.

Sources include Galway: Politics and Society 1910 - 23, by Tomás Kenny, published by Four Courts Press, Civil War in Connacht, by Nollaig Ó Gadhra, Mercier Press 1994, Margaret Collins, Marion Nikolakos, Galway Co Library archive, and War of Friends exhibition at Galway City Museum.