‘ The case is exciting intense interest, and already the sheriff is over-powered with applications for admission to the court, but the police have taken precautions to prevent any undue overcrowding’.

(Irish Times December 12 1864 )

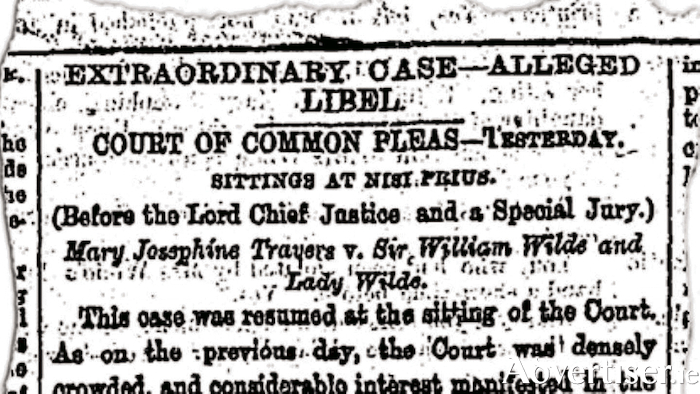

The case that held Dublin’s rapt attention for that week, concerned a long-term patient and friend of Sir William Wilde and his family, who was the daughter of a colleague, Mary Josephine Travers. It appears she and Sir William had probably enjoyed a love affair. But that intimacy had turned decidedly sour. Mary now claimed that Sir William had sexually assaulted her while she was senseless having been administered chloroform.

It was no secret that, prior to his marriage at least, Sir William had an eye for the ladies. He was known for his passionate nature. He was the father of three children born while he was still a single man: a boy, Henry Wilson, and two girls, Emily and Mary who were given their father’s surname. Sir William acknowledged paternity and provided for their education. They were reared with relatives, away from Dublin, and did not seem to bother his wife, Jane Elgee, whom he married in later life (last week’s Diary August 11 ).

His wife was well known in Dublin for her radical poems and extreme nationalist opinions urging rebellion against Britain. Under the pseudonym ‘Speranza’ her views were forcefully expressed in The Nation, before the authorities closed the paper down.

Jane was also an assertive character, and a brilliant hostess. Their dinner parties at Merrion Square were open to the good and the famous. Among writers and musicians, university professors, and government officials, you could find Maria Edgeworth, the hilarious Charles Lever, with whom Sir William had been to medical school, and the more serious poet, barrister, and antiquarian, Sir Samuel Ferguson. The Wildes were a famous and very popular couple on the Dublin social scene. They had three children, Willie, Oscar, and a girl Isola Emily. Unusually for the time, the children were allowed to mix with the house guests. No doubt Oscar’s precociousness shone on these occasions.

Lady Wilde’s letter

The previous April Mary Travers began her campaign against Wilde by displaying placards, and publishing a pamphlet in which she crudely parodied the Wildes as Dr and Mrs Quilp. She portrayed Dr Quilp as the rapist of a female patient anaesthetised under chloroform. These were sold and distributed by local newsboys, initially outside the Metropolitan Hall, in Abbey Street, where Sir William was giving a lecture; and later, when Lady Wilde took her children to Bray for a holiday, boys actually presented the leaflets to her children at the door of their residence.

Lady Wilde was intensely proud of her husband. Aware that his astonishing work-load both in his medical practice, and his antiquarian research, led him to suffer bouts of ‘physical and psychological decline’ (which had been apparent, and frequent, after his completing the classification of antiquities for the Royal Irish Society in 1857, and following the death of his two children Emily and Mary ), she decided to swing the attention away from her husband, onto herself. She did so by carefully writing a letter to Miss Travers’ father expressing outrage at his daughter’s attack: ‘You may not be aware of the disreputable conduct of your daughter at Bray, where she consorts with all the newspaper boys in the place, employing them to disseminate offensive placards in which my name is given, and also tracts in which she makes it appear that she has had an intrigue with Sir William Wilde.

‘If she chooses to disgrace herself that is not my affair; but as her object in insulting me is the hope of extorting money, for which she has several times applied to Sir William, with threats of more annoyance if not given, I think it is right to tell you that no threat or additional insult shall ever extort money for her from our hands. The wages of disgrace she has so largely treated for and demanded shall never be given to her’.

Lady Wilde’s plan worked perfectly. Miss Travers, who read the letter, was incensed at the accusation that she ‘consorted with all the newsboys in the place’ which she saw as a clear reference to some sort of sexual deviation. Her solicitor demanded £2,000 to settle the libel. Of course Lady Wilde refused, and a trial date was set for December of that year.

Background

Mary Josephine Travers became a patient of Sir William due to some trouble she had with her hearing. She was 19 years old at the time. She became a frequent visitor, a friend of the family who often minded the children. Miss Travers developed a crush on Sir William, that soon spiralled into an obsession. They exchanged letters, and probably were intimate. Wilde, however, tired of her, and tried to keep his distance. Miss Travers became desperate for his affections. She self-harmed, swallowed a bottle of laudanum in front of him which Wilde dealt with by giving her an emetic. She published her death notice in a newspaper, and showed it to Lady Wilde with some of her husband’s letters which Lady Wilde refused to read. Sir William, however, still gave her money from time to time, the so-called ‘wages of disgrace’. Lady Wilde and Miss Travers had a row, and she was banned from the house. It was then that the accusations of rape were published, and Miss Travers felt that ‘a gross libel’ had been made against her by Lady Wilde in the letter to her father.

The Trial

Miss Travers was fortunate to secure the services of the formidable Isaac Butt MP, the Irish Nationalist and founder of the Home Rule League. Butt was reckoned the most deadly cross-examiner at the Irish Bar. The Wildes retained Serjeant Sullivan and Michael Morris, later Lord Killanin of Spiddal, Co Galway.

The trial lasted five days during which Lady Wilde gave a masterful performance, denying that she gave any implication that Miss Travers was a prostitute claiming instead that Travers’ accusations were an illusion made by an hysterical young woman.

Miss Travers turned out to be a poor witness. She insisted that the court make her alleged rape by Sir William a central part of her case, even though it had no relevance to the libel charge. Yet Miss Travers became vague on the details she had written about the rape. She did recall ‘Wilde having wanted me to go to one part of the room, and he thought to drag me…. and hurt me’. On another occasion he ‘caught hold of my hand and forced me into an armchair, and said he would not let me go until I said whether I loved him or not; he said if I did love him, he would let me go at once… he bruised my fingers; there was no improper connection between us’.

Isaac Butt, however, felt that the rape accusation was clearly a central part of the plaintiff’s case. Even if it could not be proved that the rape occurred while the victim was unconscienious, even if it never happened, there was at least, as Butt said, ‘a moral chloroform that stupefied her faculties …left her senseless and prostrate at the feet of her destroyer’.

’I believe that unconsciously she was in love with Sir William …it was hinted that she was his mistress, but that was not true, his letters showed it was not true. She was driven away from the house of him whose secret she had kept - he, whose guilt she had concealed - he, whose wife she had condescended to visit, and sit at the table of the woman whose’s husband’s guilt she was concealing ….the various acts and publications charged against her were but the utterance of a broken heart.’

In his summing up the judge was unsympathetic, pointing out the inconsistencies in Miss Travers’ charges, and asked why she did not report the matter at the time. The jury were similarly unimpressed. However it found in favour of Miss Travers, that a libel had been committed, but awarded her a paltry one farthing. The costs of the case, £2,000, would be borne by the Wildes.

The reputational damage to Sir William was considerable. He was an obvious witness to the case, but for whatever reason he did not appear in court. Maybe he was unwell, and anyway during this year he was preoccupied by his next great project: the holiday home of his dreams, at Cong, on the Mayo/Galway border, overlooking upper Lough Corrib and its islands, with the majestic Maam Valley in view, There he would rest his active mind, and finish his best loved book: ‘Lough Corrib, its shores and Islands’ which is still in print today.

Next week: The Wildes escape to the west.

Sources this week include ‘The Parents of Oscar Wilde - Sir William and Lady Wilde’ by Terence de Vere White, published by Hodder and Stoughton 1967.

Would you like unlimited FREE access to all that the Galway Advertiser has to offer? Find out more here!